Sépulture de la Motte Saint-Valentin (A Grave at la Motte Saint-Valentin)

Charles Royer (1848–1920)

Langres, late 19th century

Oil on canvas

On loan from the Musée d’Orsay

Charles Royer (1848–1920)

Langres, late 19th century

Oil on canvas

On loan from the Musée d’Orsay

Anonymous

Langres, Cathedral, c. 1565

Limestone

Jean Duvet (c. 1485–c. 1560)

Langres, c. 1546–1555

Burin engraving

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652)

Rome, 1612–1613

Oil on canvas

Claude Gillot (1673–1722)

Langres, circa 1700

Etching and burin

Jules-Claude Ziegler (1804–1856)

Paris, 1839

Oil on canvas

Joseph-Paul Alizard (1867–1948)

Langres or Paris, 1900

Oil on canvas

Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746)

Circa 1685

Oil on canvas

Béligné

Langres,18th century.

Steel, silver, mother of pearl

Aprey, 18th century

Faience

Michel Dumas (1812–1885)

Lyon, 1844

Oil on canvas

Jules-René Hervé (1887–1981)

Paris, 1925

Oil on canvas

Anonymous

Langres, Saint-Mammès Cathedral?, circa 1565–1570

Limestone (from Asnières-Lès-Dijon)

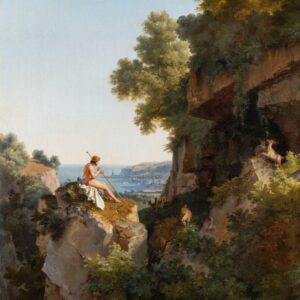

Lancelot Théodore TURPIN DE CRISSÉ (1782–1859)

Paris ?, 1827

Oil on canvas

Joseph Philibert GIRAULT DE PRANGEY (1804–1892)

1835 or 1839

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

Jules ADLER (1865–1952)

1902

Oil on canvas

Charles Le Brun (1619–1690)

Oil on canvas

Jean Tassel (1608–1667)

Oil on wood

Cornelis de Heem (1631–1695)

Oil on wood

Jean Leclerc (1587–1633)

Nancy, circa 1600

Oil on canvas

Workshop of Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

Oil on canvas